Sargy

Mann

On the eve of a posthumous exhibition in 2021, I revisited the life and legacy of the blind artist Sargy Mann for Artists & Illustrators magazine. More so than his visionary paintings, I was moved by the story of a man with a remarkable will to create.

The opening minutes of Peter Mann’s wonderful 2006 film about his late father, the artist Sargy Mann, are something of an emotional rollercoaster. Opening on a black screen, we hear a recording of Sargy’s gentle, otherworldly voice confirm that it is 30 May 2005 and today marks “the end of vision”. His eyesight had been deteriorating for more than 30 years, following cataracts and retinal detachments, and he had awoken to experience total blindness for the very first time. “I presume I won’t be painting any more pictures,” he says, seemingly in a state of shock.

Before one can even begin to contemplate the sheer injustice of an artist being robbed of his most valuable sense, his voice begins again. Nine days have passed and Sargy describes “the most perfect, soft summer morning” as he settles down to paint. He had one last primed canvas on his easel that he decided to complete as a form of closure. Fast forward a little and his voice is brighter again as he reveals that “it’s 12pm and I’ve just had, I don’t know what, the most remarkable hour and a half’s painting of my life I should think.”

A painted memory of a hotel bar in the Spanish town of Cadaqués, the evening light bouncing off the Mediterranean, came together more easily than he could ever have hoped. “Although I am totally blind now, I just see the canvas changing colour when I put the pigment down on it,” he says. “I wonder, maybe I can paint? I quite enjoyed doing it, I must say.”

Sargy’s whole life was full of these modest yet revelatory moments. He treated his diminishing sight not as a disability but rather a prompt to look harder and feel more; the inability to draw directly from life became a licence to imagine and invent. In doing so, he found new ways of seeing.

All of that was to come. Sargy’s life and career began with promise. He was born Martin Mann on 29 May 1937 in Hythe, Kent, and sent away to boarding school in Devon aged six. Accomplished in maths, science, music and even sports, Sargy only turned to art during A-Levels after a friend saw his drawings and suggested he apply to Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts. “In that instant, I realised that was what I wanted, more than anything else in the world, I’d just never admitted it to myself,” he later recalled.

He spent the early 1960s studying under the likes of Frank Auerbach and Euan Uglow, sharing a love of bold colour with the former and an appreciation of moments of everyday beauty with the latter. Even more influential was the Pierre Bonnard exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1966; Sargy visited the show 24 times, cementing a life-long obsession with the French painter. After a postgraduate degree and with the idea of finding gallery representation “laughable”, Sargy settled into teaching at both Camberwell and the Camden Arts Centre. The affable artist was helped along by the many friendships that he struck up with ease. He had played drums in a jazz trio that included Dudley Moore on piano, hung out in the same London circles as filmmaker Mike Leigh and Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett, and befriended the author Elizabeth Jane Howard, the second wife of fellow novelist Kingsley Amis.

Sargy lived with the couple for eight years, moving into their Georgian villa, Lemmons, on the outskirts of north London. Guests during that time included poet John Betjeman, novelist Iris Murdoch and a young Daniel Day-Lewis – all three would later purchase the artist’s work. When Howard organised the inaugural Salisbury Festival of the Arts in 1973, she saw to it that Sargy would have his first solo exhibition at the Wiltshire town’s Old College of Art. Works included several paintings of the bathroom at Lemmons that owed a debt to Bonnard. In his introduction to the exhibition catalogue, Betjeman noted that Sargy’s paintings “are nearly always started from a particular play of light which will lead to the main composition… The more dramatic the light, the more quickly he must record his impressions.”

The light was fading though. In that same year, Sargy underwent a cataract operation and, after marrying Frances Carey in 1976, his work briefly became darker and more abstract. Two retinal detachments in two years left him with only partial vision in one eye from 1980 onwards.

Sargy’s self-confessed “big break” came when he was introduced to Christopher Burness, founder of Cadogan Contemporary. He hadn’t had a solo exhibition for a decade when Burness visited his Peckham studio, but the dealer offered him one on the spot. “I found the work utterly compelling and central to the aesthetic I hoped to establish for Cadogan,” he told me. “We struck it off immediately.”

A successful Cadogan debut in 1987 led to a further 17 solo shows at the gallery to date. Sargy became officially registered blind the following year and quit teaching to move with his family to Suffolk. Though the artist still had very limited vision in one eye, Burness admired his openness and honesty about what lay ahead: “He was always aware he would go totally blind at some point.”

Sargy was grateful for the chance to focus on painting and his stoic pursuit of his craft was matched by the gentle sense of humour that endeared him to so many. He used tape recorders as an aide-mémoire and gave his autobiography-of-sorts the knowing subtitle, “Probably the Best Blind Painter in Peckham”. Olivia Laing’s essay for a posthumous 2019 exhibition catalogue, Late Paintings, tells of his determination to continue enjoying art while suffering severe water retention in his cornea: “He took a hairdryer to the National Gallery, plugged it in and calmly dried his soggy, waterlogged eye in order to see the paintings”.

When Sargy eventually lost the last shred of sight after the Cadaqués trip, the works that followed communicate both a warm nostalgia for family holidays past and also the very present thrill at being able to paint despite the odds. They are, as Laing put it, “testimonials to the abundant pleasures of light and space, the idle hour between swim and beer when everyone drifts into the same small room to pass the time together”. Yet the artist could only rely on visual memories for so long. Figures became a mainstay in his works as he used their fixed proportions to help map out three-dimensional space in paint. He marked out the proportions of his wife Frances on a stick as a guide and used that to help plot out key points on the canvas in Blu Tack before painting between them.

The final decade of his life became perhaps the most creative period of his career. “Blindness has given me the freedom and courage to risk degrees of inventiveness I would not have dared take before,” he told Artists & Illustrators in 2006. Bonnard’s example led him once more through the darkness. In an early sketchbook, Sargy had repeated the French painter’s claim that he was “weak in front of nature” and quoted him as saying: “The presence of the object, the motif, is very cramping for the painter at the moment of painting.” Sargy himself had no choice but to heed these words. Freed from such strictures, he was finally able to map out his own little worlds from the comfort of his garden studio.

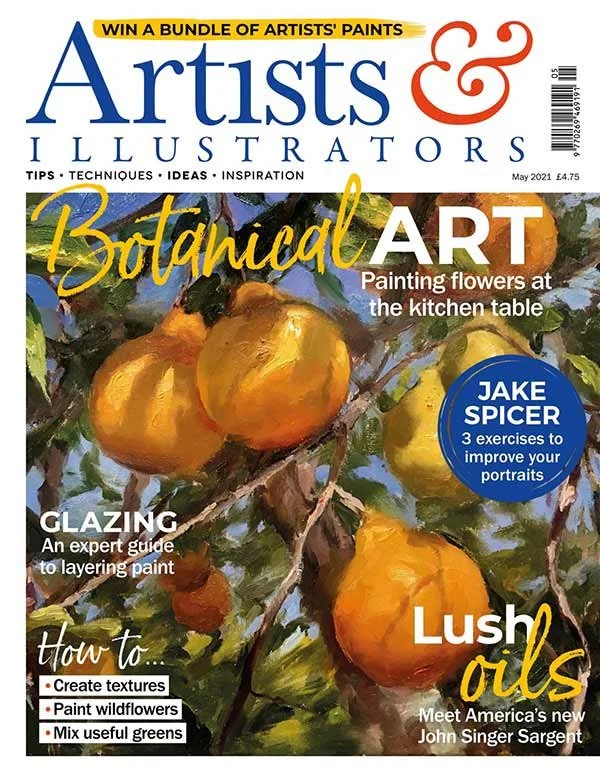

This article was originally published in issue 429 of Artists & Illustrators, May 2021. All images © Sargy Mann Archive/Cadogan Contemporary.

Sargy Mann, Lemmons, Bathroom Window, c.1972, oil on canvas

Sargy Mann, Garden Wall in Sun, 1968, oil on canvas

Sargy Mann, Figures by a River, 2014-’15, oil on canvas